The gap between what you intend and what they experience

Key Takeaways:

- Your position amplifies everything. A casual comment becomes a directive. Silence becomes evasion. Your team experiences your words and your silence louder than you think.

- Clarity is an illusion. You live inside the decision. Your team doesn’t. What feels like transparency to you often lands as corporate-speak or deliberate avoidance to them.

- Competence isn’t enough. Technical brilliance got you promoted. But without self-awareness, you’ll deliver results with broken people and wonder why they’re leaving.

Mark was a good manager. His team would tell you that. He cared about their development, fought for their budgets, genuinely wanted them to succeed.

So when half his team applied for internal transfers within six months, he was blindsided.

“I thought we were in a good place,” he told HR. “I’d just approved their training budget requests. I’d been completely transparent about the quarterly numbers.”

The exit interviews told a different story. His “transparency” about falling revenue felt like a warning they were all expendable. His approved training budget felt like a consolation prize before layoffs. His “open door” felt like a trap door; they never knew which version of Mark they’d get. The approachable coach on Monday became the stress-case who went silent for three days after Tuesday’s exec meeting.

When he mentioned “tightening our belts” in the team huddle, he meant they should be mindful of expenses. They heard: redundancies are coming. Within 24 hours, they were swapping job links in a WhatsApp group he knew nothing about.

Mark wasn’t a bad leader. He was a blind one.

This is the modern leadership trap. Good intentions, real care, genuine expertise and still, teams feel alienated. Not because leaders lack empathy or skill, but because they misread how their position changes the impact of their behavior.

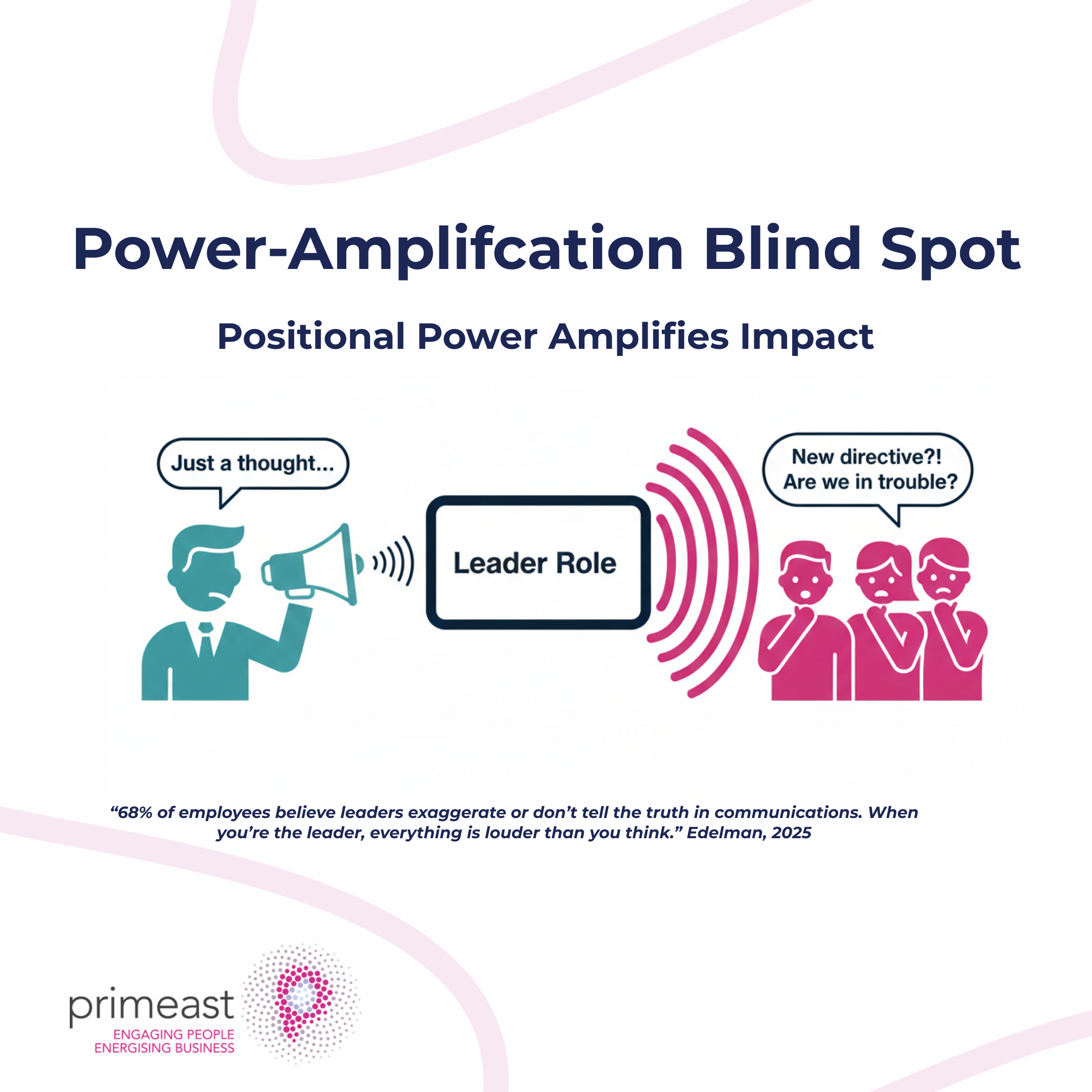

The gap between intent and impact has never been wider. And in a climate where 68% of employees believe leaders exaggerate or withhold the truth, even well-meaning managers are losing their teams without knowing why.

When Intent and Impact Part Ways

Your team doesn’t experience your intentions. They experience your behavior. And the higher you climb, the wider that gap becomes.

The 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer shows an unprecedented decline in employer trust. Fear that leaders deliberately lie jumped 12 points in a single year. Only 21% of employees globally say they’re fully engaged, poor listening and inconsistent communication are major drivers.

This isn’t about toxic leadership. Most articles focus on the obvious villains: the bullies, the narcissists, the micromanagers. The more insidious problem is the capable, caring leader who simply doesn’t see how they’re landing.

Managers account for 70% of the variance in employee engagement. Yet only 31% feel engaged themselves. Stressed, stretched, operating from their own internal script, they miss what their teams actually need.

Three blind spots show up again and again….

The Power-Amplification Effect

Your intent: “I’m just doing my job.”

Their experience: “You’re steamrolling us.”

The moment you become someone’s manager, everything you say gets louder. A casual observation becomes a directive. A suggestion feels like an order. A raised eyebrow in a meeting can silence a room.

Most leaders underestimate this. They remember what it felt like to be a team member, so they assume their words land the same way now. They don’t.

Research on positional power shows that managers are routinely late in recognising the need for change, while employees closest to problems are discouraged from speaking up. The power dynamic itself creates a feedback vacuum.

Silence is just as amplified as speech. When leaders go quiet to “avoid creating noise,” employees fill that vacuum with anxiety and worst-case stories. A leader who thinks they’re being measured is experienced as evasive. A leader who thinks they’re letting the team “get on with it” is experienced as absent.

Consider Morrisons in early 2026. Leadership stuck to the National Living Wage for pay increases, a decision they saw as fiscally responsible. They announced it in an email that emphasized “competitive market positioning” and “long-term sustainability.” No mention of the staff who’d worked through chronic understaffing, covered shifts during labor shortages, or dealt with aggressive customers during the cost-of-living crisis.

Staff described it as “tone deaf.” The alienation wasn’t the decision itself. It was that leaders seemed not to grasp what employees had sacrificed or what they needed to hear.

Intent: we’re being prudent stewards. Experience: you don’t see us at all.

The self-awareness shift:Because of my role, everything I say is louder than I think. I need to be intentional about how I use my voice and, often more importantly, my silence.

The Clarity Illusion

Your intent: “I’ve been crystal clear.”

Their experience: “We don’t know what’s going on.”

Leaders often believe they’ve communicated thoroughly. They’ve said it in the all-hands. They’ve put it in the email. They’ve mentioned it in three separate meetings. Job done.

Except only 47% of employees strongly agree they know what’s expected of them. And 40% say their trust in leadership drops when communication feels inconsistent or unclear.

The problem isn’t volume. It’s perspective. Leaders live inside the decision, they know the context, the trade-offs, the reasoning. Their teams don’t. What feels like a clear explanation often lands as corporate-speak, vague reassurance, or deliberate evasion.

Boeing’s 2024 crisis communications became a case study in this gap. When CEO Dave Calhoun released a pre-recorded statement rather than taking live questions about the Alaska Airlines incident, he thought he was being measured and precise. He wanted to avoid saying something he’d regret.

The public, and Boeing’s own employees, experienced a lack of empathy and an absence of detail. Within 48 hours, internal forums filled with comments like “He’s hiding” and “We’re on our own.” Employees needed to hear their CEO acknowledge the gravity of what happened and outline specific next steps. Instead, they got careful corporate messaging. Silence and scripted statements are interpreted as hiding something. And in Boeing’s case, the gap between what leadership knew and what they’d say would take months to close.

The same pattern plays out in smaller moments every day. Return-to-office mandates announced without explaining the why. Restructures communicated through corporate memos that answer questions nobody asked while ignoring the ones everyone has. Pay decisions framed as strategic when employees experience them as personal.

The self-awareness shift:Before sending that email or walking into that meeting, ask three questions:

- What will they actually hear when I say this?

- Where might this feel vague, unfair, or sugarcoated?

- Have they had a chance to give input or at least react?

Competent but Not Self-Aware

Your intent: “I’m driving performance.”

Their experience: “You’re breaking us.”

Many leaders are technically brilliant. They were promoted because they delivered results, solved problems, outperformed their peers. But technical competence doesn’t automatically translate to relational intelligence.

Research following 12 executives who worked under leaders with low self-awareness found that all of them created cultures of fear. One respondent put it bluntly: “He delivers the results, but he delivers it with broken people.”

Most of those employees started looking for another job within six months.

The behaviours are often subtle. “Passionate” comes across as aggressive. “High standards” feel like impossible demands. “Direct” feels like bulldozing. The leader sees drive; the team experiences damage.

Consider two managers in the same organisation. The first insists, “People know I care, I push them because I believe in them.” But he’s never asked how his style lands. Turnover in his team runs at twice the company average.

The second says in a team meeting: “I know when I’m under pressure I can get abrupt. How do you experience me, and what would help?” That single question, honest, vulnerable, specific, shifts the conversation entirely. It signals that feedback is safe. It opens space for the team to co-design how they work together.

Self-aware leaders name their patterns. They say things like, “When I’m stressed, I tend to go quiet” or “I know I can jump to solutions, call me out if I’m not listening.” They don’t wait for feedback; they actively invite it.

The self-awareness shift:The self-awareness shift: Move from “competent operator” to “conscious shaper of experience” by developing three layers:

- Mindset: Notice your stories about performance and people. What assumptions are you making?

- Skillset: Practice specific behaviors, listening before solving, asking before telling, framing before deciding.

- Heartset: Build the courage and humility to hear the truth and change course.

Self-Awareness as Practice, Not Personality

Self-awareness isn’t a fixed trait. It’s a practice. Something leaders can develop, not through more content or frameworks, but through experiencing themselves as others experience them.

That’s the gap in most leadership development. Knowing about emotional intelligence doesn’t make you emotionally intelligent. Reading about feedback doesn’t change how you receive it. Understanding power dynamics doesn’t help you feel how your presence lands in a room. What changes behavior is practice, with real feedback, in real time, under real pressure. It’s experiential, not theoretical. And it’s measurable, not aspirational.

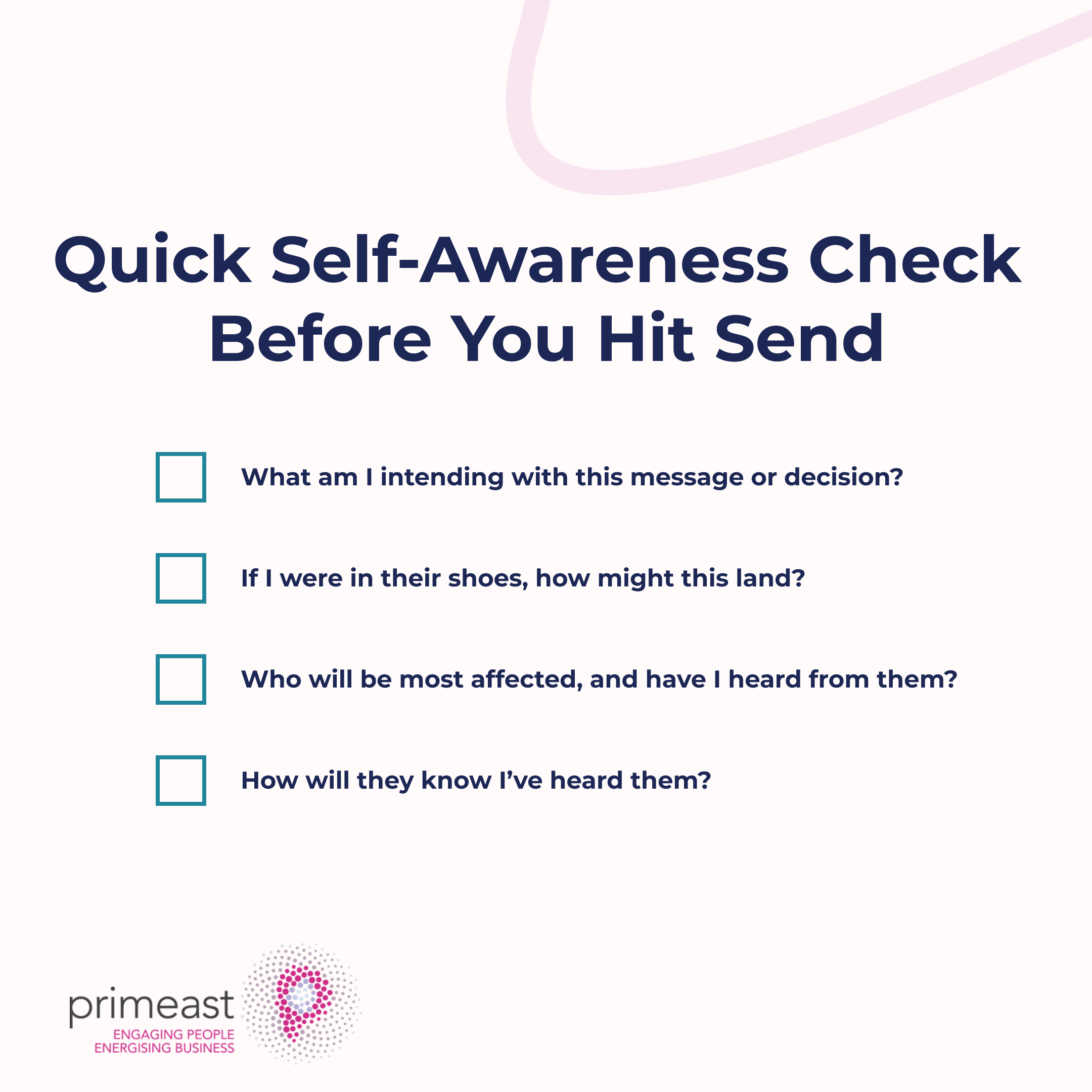

Before your next meeting, try these four questions:

- What am I intending? Name it explicitly, to yourself and to them.

- If I were in their shoes, how might this land? Perspective-taking before speaking.

- Who will be most affected and have I heard from them? Voice and inclusion.

- How will they know I’ve heard them? Action, not just words.

Good leaders don’t alienate their teams on purpose. They do it by accident, through blind spots they’ve never examined. The ones who close the gap between intent and impact aren’t necessarily smarter or more empathetic. They’re simply more aware of themselves in relation to others.

That awareness can be developed. But it requires more than good intentions. It requires taking relational leadership to the next level.

Primeast develops leaders, teams, and cultures to thrive in a fast-changing world. Our experiential approach helps leaders see themselves clearly, and change the behaviors that matter most. Contact us today.